Australia Said No to big tech.

Dr Michael Carr-Gregg, AO

February 3, 2026

This week, Big Tech is on trial in the United States — and childhood is the evidence. For years, parents were told they were overreacting. Teachers were told they didn’t “get” technology. Clinicians were told the evidence was “mixed”.

Now a courtroom is asking a different question: What did tech companies know about harm to young people — and what did they do anyway? Let’s be clear: this is not a debate about screen time. It never was. It’s about design choices — engineered to maximise engagement, emotional reactivity, comparison and compulsive use, all during the most vulnerable period of brain development.

This isn’t accidental. Internal documents already show that adolescent psychology wasn’t ignored — it was systematically studied, understood, and leveraged. Reward sensitivity, novelty-seeking, poor impulse control, sleep deprivation and identity formation weren’t protected. They were monetised.

For a decade, the defence has been familiar:

• “The evidence is inconclusive”

• “Correlation isn’t causation”

• “Most kids are fine”

All technically true but morally insufficient. In public health and psychology, we don’t wait until every child is harmed before acting. We intervene when risk is predictable, preventable, and scalable. This trial matters — not just legally, but culturally. It validates what the Australian Government, schools, families and clinicians have been observing for years: rising anxiety, sleep disruption, aggression, loneliness and distress didn’t appear out of nowhere. It also sends an important message to young people themselves:

You are not broken.

Your brain did not fail.

You were up against systems designed to be irresistible. Be clear, litigation alone won’t fix this. Childhood moves faster than courts. But this moment forces a long-overdue reckoning about responsibility, regulation, and whether powerful companies owe a duty of care to developing minds. Because the real question isn’t whether social media is “good” or “bad”. It’s this: What responsibility do corporations have when their products shape childhood — and what happens when they get it wrong? I hope decision-makers are paying attention.

Special Award for Dr Michael Carr-Gregg, AO

SchoolTV’s founding psychologist, Dr Michael Carr-Gregg AO, has been recognised as an Officer of the Order of Australia for his distinguished service to child and adolescent psychology, policy reform, youth cyber safety and the broader community.

This is an exceptional and thoroughly well-deserved honour, reflecting decades of advocacy, leadership and tireless commitment to improving the mental health and wellbeing of young people and families across Australia.

To mark the occasion, Michael has recorded a short video message reflecting on the importance of prevention, mental health literacy and the collective impact we are making together through SchoolTV.

We are incredibly proud to work alongside Michael and grateful for all our trusted school partnerships that support families, staff, and students. @Australian Honours and Awards @Council for the Order of Australia hashtag#SchoolTV hashtag#Wellbeing hashtag#MentalHealth

We are failing our girls — and the boys who hurt them - A candid voice on youth, schools and responsibility

Scott Galloway’s Notes on Being a Man lands at a moment of national discomfort. His blunt interrogation of modern masculinity — its anxieties, entitlement and performance — should be required reading in staff rooms and living rooms alike. Because when teachers in our schools are being barked at, sexually harassed and threatened with violence, Galloway’s arguments aren’t abstract cultural critique — they’re a direct indictment of a generation of boys being socialised into cruelty.

The Monash study revealing that female teachers are routinely humiliated, groped, surrounded and baited with manosphere rhetoric should shock every parent who thinks “that sort of behaviour” happens somewhere else. It doesn’t. It is happening where we send our children every day to learn respect, problem‑solve and grow. Instead, too many boys are graduating from online echo chambers preaching dominance, then practising it in classrooms. That is societal malpractice.

Galloway prompts us to ask: what does being a man mean if it involves degrading others to prove yourself? The answer should be obvious: nothing worth preserving. Schools cannot be left to mop up the mess of fractured home cultures, absent fathers, toxic influencers and a viral pornography economy that normalises objectification. And yet the study shows many teachers’ cries for help are met with bureaucratic shrugging — “noted”, “logged”, then forgotten.

Practical steps are not radical. We need clear, enforceable protocols that treat gendered threats as seriously as weapons. We need mandatory, evidence‑based respectful relationships education delivered early and repeated across years. We must fund counselling and behavioural programs for students who display misogyny as a red flag, not merely punish them into resentment. And parents need to be dragged, willingly or not, into the work of modelling empathy, accountability and emotional literacy.

Finally, stop pretending this is only a school problem. It’s cultural. Galloway’s call for men to reject the currency of dominance must be matched by our institutions: schools, sporting clubs, platforms and courts. If we produce men who equate power with humiliation, we will continue to pay the cost in broken classrooms, devastated teachers and, worse, lives.

The country that fails to teach decency to boys will one day be shocked by what its boys have become. Every father should read Galloway, listen to our teachers, and act — now.

Violence in Schools Isn’t a Behaviour Problem. It’s a System Failure

Dr Michael Carr-Gregg, AO Child & Adolescent Psychologist, Author, Founding member CanTeen, Founding psychologist SchoolTV, Patron of Read the Play

February 2, 2026

More than 50 years ago, when I was a 10-year-old student at Dulwich College Preparatory School in London, an older boy punched me in the stomach without warning as I walked across the playground at lunchtime. I collapsed. I couldn’t breathe. I was rushed to King’s College Hospital and spent two days in ICU with a diaphragmatic rupture — a potentially fatal injury. Nothing happened to the boy who did it. His parents were never contacted. The school carried on as if nothing had occurred.

That memory came flooding back this week as I read the Monash University report in which Australian school principals describe their working lives as a “nightmare”. How is it possible that, half a century later, we are still here? The surge in violence in schools is no longer about “challenging behaviour”, poor classroom management, or a few isolated incidents. It is systemic failure — and educators are carrying the risk for all of us.Teachers and principals are being punched, bitten, stalked online, threatened, and harassed. Cars are vandalised. Homes are targeted. And increasingly, the perpetrators are not just students, but parents and extended family members — often acting with little fear of consequence.

For years, schools have been told to manage escalating violence through restorative practice, trauma-informed approaches and individual behaviour plans. These are important tools — but they were never designed to replace authority, accountability or basic safety. You cannot restorative-conversation your way out of a punch to the stomach. Nor can you “co-regulate” while being threatened or assaulted. What troubles me most is the silence that surrounds this issue. Principals speak of slow departmental responses, legal frameworks that prioritise offenders over victims, and a quiet but dangerous message: cope, absorb, don’t escalate. When violence is absorbed without consequence, it becomes normalised. When fear becomes part of the job, experienced leaders leave — burnt out, traumatised, and unheard. Let me be clear: many of the young people involved are profoundly vulnerable. Trauma, neurodivergence and disadvantage demand compassion and skill. But compassion is not permissiveness. Trauma does not excuse violence. And vulnerability does not remove responsibility.

A civil society draws lines — especially to protect those who serve it. Schools need clear escalation pathways. Principals need immediate backing when safety is threatened. Teachers need assurance that reporting violence will lead to protection, not professional risk.Abuse of school staff is unacceptable. Full stop. This is not about being “tough on kids”. It is about being honest with adults. If experienced school leaders are dreaming about being attacked at work, something has gone deeply wrong. The question is no longer whether violence in schools is increasing. It’s how long we are prepared to tolerate it — and who we are willing to let pay the price while we look away.

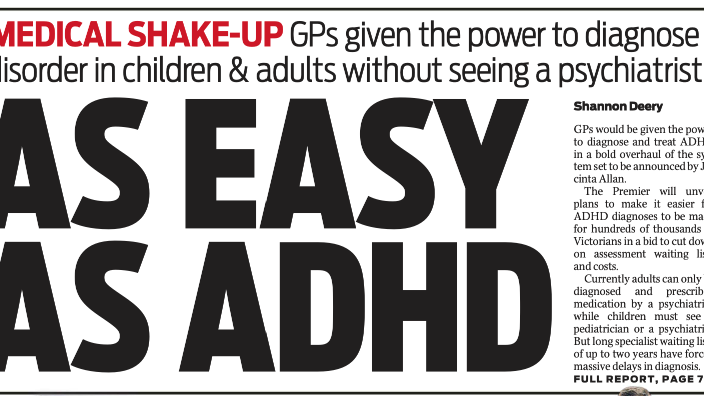

Finally, We’re Trusting GPs With ADHD. About Time.

Dr Michael Carr-Gregg AO, February 3, 2026

The Victorian government has announced that GPs will now be allowed to diagnose and treat ADHD in adults and children as part of reforms to reduce long waits and high costs for specialist assessment. The announcement includes an initial investment to train around 150 GPs by September 2026 so they can expand their scope to safely diagnose, treat and prescribe for ADHD. Putting aside the fact that four other states/territories (Queensland, NSW, WA, and SA) had either already implemented or announced reforms - this is a great move.

Cue the pearl-clutching. Cue the think pieces about “over-diagnosis.” Cue the sudden concern for patient safety from people who have never tried to book a psychiatrist or a paediatrician in this state. But for anyone who actually lives with ADHD — or loves someone who does—this reform isn’t radical. It’s long overdue.

For years, ADHD has been treated like a niche, specialist-only condition, as if recognising a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder requires a crystal ball and a three-year waitlist. Adults have been bounced between referrals, told their symptoms are “stress,” “anxiety,” or a personality flaw, and left untreated while their lives quietly unravel. Parents have watched their kids struggle at school while paperwork crawls through a system designed for scarcity, not care.

All the while, the evidence has been clear: ADHD is common, well-researched, and treatable. And GPs—who already diagnose and manage depression, anxiety, diabetes, asthma, and countless other chronic conditions—are more than capable of doing this work. The idea that only psychiatrists can safely diagnose ADHD has never really been about safety. It’s been about gatekeeping.

In Victoria, opposition or strong caution about expanding GPs’ role in diagnosing and treating ADHD (especially prescribing stimulants) has mainly come from psychiatrists (via their professional bodies. Let’s be honest about what the old system produced. It didn’t protect patients; it delayed care. It didn’t ensure rigour; it ensured privilege. If you had money, time, and the ability to navigate a labyrinth of referrals, you got help. If you didn’t, you were told to cope better, try harder, or wait another year. That’s not clinical excellence. That’s rationing dressed up as caution.

GPs are already the backbone of our health system, especially for children and teenagers. They know their patients. They see the full picture—mental health, physical health, family context, history over time. They are often the first to suspect ADHD, and until now, they’ve been forced to stop just short of actually helping. This reform closes that absurd gap.

It also reflects a reality policymakers have been slow to accept: ADHD doesn’t magically appear in childhood and vanish at 18. Adults have ADHD. Women have ADHD. People who weren’t disruptive at school, who internalised their struggles, who masked and compensated and burned out quietly—have ADHD. These are the very people most likely to fall through a specialist-only system.

Critics warn this change will lead to “over-diagnosis.” But what they really mean is more diagnosis. And when a condition has been systematically under-recognised for decades, that’s not a problem—it’s a correction. We don’t accuse GPs of “over-diagnosing” asthma because more people get inhalers. We don’t panic about “too much depression” when antidepressants become more accessible. We recognise unmet need. ADHD should be no different.

Of course, this doesn’t mean every GP suddenly becomes a lone cowboy/cowgirl handing out scripts. Training, guidelines, and clear pathways matter. Complex cases will still need specialists. Safeguards should exist. None of that is incompatible with trusting GPs to do what they already do every day: assess, diagnose, monitor, and refer when needed. What is incompatible is a system that treats ADHD like a rare indulgence instead of a mainstream health issue.

This reform is about more than efficiency. It’s about dignity. It’s about believing patients when they describe their own lives. It’s about recognising that long waitlists are not a virtue, and suffering is not a prerequisite for care. Victoria hasn’t lowered the bar. It’s removed an unnecessary wall. And for thousands of people who’ve spent years stuck on the wrong side of it, that’s not just policy. It’s relief. Finally.

Young people aren’t reckless. They’re confused — and we’ve left them that way.

Dr Michael Carr-Gregg AO

February 4, 2026

Child & Adolescent Psychologist, Author, Founding member CanTeen, Founding psychologist SchoolTV, Patron of Read the Play, Accredited Mental Health First Aid Trainer

February 4, 2026At first glance, the latest survey from the Burnet Institute looks reassuring. Young people are drinking less. They know vaping is harmful. They are, on paper at least, more health-literate than any generation before them. And yet the same young people are vaping in record numbers, using harder drugs more frequently, and remain dangerously misinformed about sexual health. The Burnet Institute’s Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll survey reveals something far more troubling than “risky youth behaviour”. It exposes a widening chasm between what young people know and what they are actually able to do in the real world.

Take vaping. Young people rated its harmfulness at a staggering 89 out of 100. Yet nearly two-thirds still use e-cigarettes. That’s not ignorance. That’s addiction meeting accessibility, peer pressure and stealth marketing — in an environment where anaemic regulation lags years behind reality. As Associate Professor Megan Lim rightly points out, knowledge alone isn’t enough. Expecting awareness to trump addiction is like handing someone a fire safety brochure and sending them into a burning building.

Then there’s sex education — or rather, the absence of it. Despite unprecedented access to information online, many young Australians lack basic, practical understanding of sexual health, consent and sexually transmitted infections. Porn has become the lead sex educator for young people. Social media fills the gaps. Silence does the rest. We should stop pretending that “they can Google it” is a public health strategy.

The drug data is equally worrying. Seven in ten respondents have used illicit drugs. Cocaine and ketamine use are rising, even as MDMA declines. The Alcohol and Drug Foundation reminds us that nationally, drug use is “stable” — but stable does not mean safe, especially for the developing brain. And here’s the irony: at the same time as drug use remains high, alcohol consumption is falling sharply. Research from Flinders University shows Gen Z are far more likely than Baby Boomers to abstain from alcohol altogether.

This matters. It tells us young people are capable of behaviour change when the environment supports it. We restricted alcohol advertising and promotion, (sporting events still have a loophole) but alcohol is harder to glamorise now. Drink-driving laws are clear. Social norms have shifted. Messaging has been consistent. We haven’t done the same for vaping, hard drugs or sexual health. Instead, we’ve relied on fear-based messaging, patchy education, and the comforting myth that young people will simply “make better choices” if we warn them loudly enough. They won’t — because no generation ever has.

Which is why the Victorian Premier’s reported consideration of abolishing the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation is not just short-sighted, it is insanity. VicHealth has arguably done more for adolescent health promotion than any other organisation in the state: driving shifts in attitudes to smoking and alcohol, funding school- and community-based programs, and building exactly the kind of long-term, evidence-based prevention infrastructure this survey says we need more of, not less. Dismantling that capacity at the very moment we are asking young people to navigate more complex risks than ever would widen the gap between knowledge and action even further.

If we genuinely care about youth wellbeing, we need to move beyond awareness campaigns and into structural action: tighter regulation of vaping products, modernised and mandatory sex education, honest harm-minimisation frameworks, and adults who are willing to talk — plainly and often — about risk, pleasure, consent and consequence.

Young people are not broken. The system around them is. And until we fix that, surveys like this won’t shock us — they’ll simply confirm what young people already know: they are navigating adult-level risks with child-level support. That is the real disconnect.

Why the age your child gets a smartphone matters more than we thought

A new study published in the esteemed medical journal Pediatrics has landed with a thud — and it should give every parent, educator and policymaker pause for thought.The study, titled 'Smartphone Ownership, Age of Smartphone acquisition and health outcomes in early adolescence' was conducted by researchers from multiple institutions. It used data from the adolescent brain cognitive development study a long term research project tracking child development in the US.

The findings are stark: Adolescents who owned a smartphone by around age 12 showed higher rates of depression, poorer sleep and increased obesity compared with peers who didn’t. Even more concerning, the earlier the phone arrived, the worse the outcomes. This isn’t about moral panic. It’s about developmental timing.

Early adolescence is not just a smaller version of adulthood. It is a “high-gain” period — supports and stresses both have amplified effects. Timing matters. What parents introduce (or delay) during this window can shape mental health trajectories for years to come. Think of it as a neurodevelopmental construction zone. Sleep architecture is changing. Emotional regulation is fragile. Identity, self-worth and peer comparison are under active construction. When parents introduce a powerful, always-on device at this stage, it turns out that they are not adding a neutral tool — they are reshaping the environment in which development occurs. And the risks compound.

Smartphones don’t just displace sleep; they fragment it. They don’t just connect peers; they intensify comparison. They don’t just entertain; they train attention away from boredom, reflection and recovery. We have spent years reassuring ourselves that “kids will adapt” — but here's the thing, it turns out that biology doesn’t negotiate. The adolescent brain develops on its own timetable, not Silicon Valley’s product cycle.

What this study adds to the conversation we have been having in Australia, is not shock value, but clarity. It strengthens a growing evidence base (that Big Tech are keen to dispute), suggesting that earlier exposure carries measurable health costs, at exactly the point when young people are least equipped to self-regulate. This doesn’t mean banning technology. It means sequencing it better.

Just as we don’t hand car keys to a 12-year-old because “they’ll need them eventually”, we shouldn’t pretend that earlier access to smartphones is harmless simply because it’s common. The real question is no longer “Can kids handle smartphones?” It’s “At what age does the cost outweigh the benefit?” And now we know.

My advice to parents contemplating buying their 12 year old a smartphone, is this: if you genuinely care about your child's mental health, sleep and physical wellbeing, you need to stop framing this as a lifestyle preference and start treating it as a public health issue. Delay is not deprivation. In many cases, it’s protection.

— Michael Carr-Gregg AO Child and Adolescent Psychologist

The Young People We Forget After Suicide

Four months after her estranged father took his own life, a 15-year-old girl sits across from me in my consulting room. She doesn’t cry. She doesn’t rage. She doesn’t ask why. She simply tells me she’s tired.

Four months after her estranged father took his own life, a 15-year-old girl sits across from me in my consulting room. She doesn’t cry. She doesn’t rage. She doesn’t ask why. She simply tells me she’s tired.

It’s a sentence I hear with increasing frequency — not just from teenagers who have lost a parent, but from those who have lost a friend. In Australia, we speak at length about preventing suicide, and rightly so. But what we rarely talk about are the young people left behind. The sons, daughters, classmates and teammates who wake up the next morning carrying questions they can never get answered. Suicide doesn’t just end one life. It radiates outward — into families, schools, footy teams, group chats, gaming communities and entire peer groups. And those caught in the blast are often the least supported, the least noticed, and the least understood. Whether the person lost is a parent or a close mate, young people often experience grief that is complicated, contradictory and deeply unsettling. Most deaths provoke sadness. Suicide triggers something much more layered. Teenagers ask themselves questions that cut straight to the bone: “Should I have seen the signs?” “Could I have stopped it?” “Was I not worth staying for?” “Why would someone my age do this?” These thoughts aren’t rare; they are overwhelmingly common. And they can be devastating. Research from around the world shows that teens bereaved by suicide — whether of a parent or friend — are at significantly higher risk of anxiety, depression, substance use, school refusal and, most concerning, suicidal ideation. When someone your own age or someone who created you dies this way, it can distort your understanding of what is possible or even thinkable.

For young people who lose a parent they weren’t close to, or a friend they’d recently fallen out with, the emotional maze becomes even more complex. “How do I grieve someone who wasn’t really there?” “Is it wrong to feel numb — or even relieved?” “Am I allowed to be angry at them?” These are normal questions, but because we don’t talk about them, young people often feel they’re grieving “incorrectly”, adding shame to an already overwhelming experience. When a child loses a friend to suicide, parents often feel uncertain, overwhelmed or frightened. They want to say the right thing but fear saying the wrong one. They are grieving too — grieving their child’s innocence, their own sense of safety, the realisation that their teenager’s world is far more complex than they imagined. But teenagers do not need perfect sentences. They need calm. Predictability. Honesty. A sense that the adults around them can withstand powerful emotions without collapsing or panicking. Presence beats perfection every time.

If there is one message I’d deliver to every principal and teacher in Australia, it is this: a student grieving after suicide must not be left to drift. Young people rarely walk into a school office and announce they’re falling apart — they show it through slipping grades, irritability, withdrawal, lateness, zoning out, or simply looking “different” in ways only attentive adults pick up. Whether the loss was a parent or a friend, schools must be actively, deliberately supportive. That means assigning a designated safe adult on staff — someone the student knows they can approach without judgement. It means monitoring academic performance, not to penalise them, but to catch the early signs of struggle. It means maintaining predictable routines, because structure is comforting when the rest of their world feels chaotic.

It also requires compassionate flexibility: extensions where appropriate, reduced homework loads, quiet spaces when needed, and an understanding that emotional dysregulation is part of trauma, not “acting out”. Schools must keep clear lines of communication with home, checking in with parents about mood, sleep, behaviour changes and social dynamics. And most importantly, teachers must understand that a drop in concentration, motivation or behaviour after a suicide is not defiance. It’s grief. It’s the brain’s executive functioning going offline under the weight of trauma.

Doing nothing isn’t neutral. It is, in fact, one of the most damaging responses a school can offer. When adults pull back, assume the young person is coping, or expect them to “soldier on”, students interpret it as a message: no one sees me. Early, proactive support isn’t a luxury — it’s a protective factor that can prevent depression, school refusal, substance use and even further suicide risk. Schools can’t undo the tragedy, but they absolutely can determine whether a young person feels held — or alone — in its aftermath. Our suicide-prevention strategies are improving, but our postvention response in schools — the care for those left behind — is patchy at best. Every child affected by suicide deserves timely counselling, coordinated care, school-based monitoring, follow-up for at least a year. Right now, it’s a postcode lottery. Many receive no formal support at all.

The 15-year-old girl in my office — exhausted, polite and doing her best — deserved more than silence. So do the countless teenagers mourning a friend whose death makes no sense to them. If we truly care about young people, we must stop treating suicide as the end of a story. For those left behind, it is the beginning of a long and vulnerable journey. And we have a moral responsibility to walk it with them. Anything less risks failing them twice.

PARENTS — IT’S TIME TO GET OUR KIDS BACK INTO THE REAL WORLD

On December 10, Australia will take one of the most significant steps in child protection we’ve seen in decades: banning social-media platforms from allowing under-16s to create or maintain accounts.

On December 10, Australia will take one of the most significant steps in child protection we’ve seen in decades: banning social-media platforms from allowing under-16s to create or maintain accounts.

Predictably, the tech giants are complaining. Influencers are wailing. Even some teenagers are staging tiny (and frankly adorable) digital rebellions.

But this isn’t a moment for parental panic.

It’s a moment for leadership.

Because for far too long, social media has been raising our children — and not doing a very good job of it.

As a child and adolescent psychologist, I’ve spent nearly four decades listening to what young people tell me behind closed doors. I can tell you this: nothing has warped childhood more than the algorithmic slot machines sitting in their pockets.

And yes — removing that digital dopamine drip is going to cause withdrawal, pushback and dramatic sighing worthy of a Netflix teen drama.

But here’s the good news:

You can absolutely do this.

And your kids will thank you for it — eventually.

1. Talk to your kids BEFORE December 10

Don’t wait until Instagram or Snapchat locks them out.

Sit down — no phones, no screens — and say something like:

“This new law is about protecting young people, not punishing them. Your job is to grow up safely. My job is to help you do that.”

Be firm. Be calm. Be collaborative.

This is not the moment for apologetic parenting.

2. Expect grief — but don’t negotiate reality

When social media disappears, many kids will go through the same psychological stages I see when I ask teens to detox:

Denial

Anger

Bargaining (“But what if I just check TikTok for homework?”)

Sadness

Acceptance

Your job is to shepherd them through this process, not install loopholes.

3. Replace the online world with the real world

Children don’t cope well with a vacuum — they fill it.

So YOU help fill it with what childhood used to have in abundance:

Board games. Card games. Real conversations. Cooking. Music. Walking the dog. Crafts. Sport. Riding bikes. Learning a skill.

Remember those? They still exist — and they’re still brilliant for developing brains.

In my consulting room, the teens who thrive are the ones whose parents invest in real-world rituals:

family dinners

weekend activities

shared hobbies

bedtime reading

even a Sunday morning café hot chocolate

These are not quaint relics. They’re protective psychological architecture.

4. Reintroduce boredom — yes, boredom

One of the greatest gifts you can give your child is the ability to be bored.

Boredom is the birthplace of creativity, problem-solving and resilience.

Social media never allowed boredom — it surgically removed it.

On December 10, boredom becomes your new best friend.

5. Prioritise connection, not supervision

Don’t turn your house into a surveillance state.

Turn it into a family.

Talk. Walk. Play. Listen.

Model offline life.

Show them what joy looks like without a screen glowing between two people.

Our kids don’t need a digital parole officer.

They need adults who are present.

6. Remind them: Their value is not measured in likes

For a whole generation, self-worth has been tied to algorithms designed by Silicon Valley engineers who wouldn’t let their own children near the products they built.

December 10 is your chance to reclaim the narrative.

Tell your child:

“You are worth more than any number on a screen. Real people who love you matter far more than strangers who scroll past you.”

7. Make December 10 turning point, not a punishmen

Celebrate it.

Mark it.

Create a family tradition:

a board-game night

a special dinner

a digital-detox day

a picnic

or a sunset walk

Let your child feel the shift not as a loss, but as a return —

a return to childhood as it was meant to be:

messy, playful, creative, curious, connected.

On December 10, the Australian Government will unplug the algorithm from our children.

But it’s up to parents to plug them back into life.

And I can promise you this:

Twenty years from now, your children won’t remember the likes they lost.

But they will remember the conversations you had, the walks you took, the games you played, and the time you gave them.

That’s the stuff that builds resilient kids — and lifelong humans.

Now’s our chance.

Let’s take it.

What My Favourite Movie Scenes Taught Me About Being Human

I’ve spent most of my professional life listening to stories — often difficult ones — in

the quiet of a consulting room. But sometimes the most powerful lessons about

human behaviour arrive not from a patient, a textbook, or a clinical trial, but from the

movies.

I’ve spent most of my professional life listening to stories — often difficult ones — in the quiet of a consulting room. But sometimes the most powerful lessons about human behaviour arrive not from a patient, a textbook, or a clinical trial, but from the movies.

Certain scenes have lodged in my memory for decades because they distil complex psychological truths into a few luminous minutes of dialogue, silence, or song. Here are a handful that continue to shape how I think about the goodness, truth and beauty of being human — and why, even after years of psychology, I still believe that good cinema is therapy for the soul.

The West Wing — “Leviticus 18:22”

When President Bartlet played by Martin Sheen calmly dismantles a bigoted radio host (Linda Carlson) by quoting other Old Testament absurdities, it’s a masterclass in moral reasoning. Rather than rage, he uses wit, intellect and evidence. As a psychologist, I love this scene because it models cognitive dissonance reduction — challenging prejudice with logic while maintaining composure. It’s persuasion without humiliation, empathy without appeasement.

Casablanca — “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

In 2002, the American Film Institute released a list of their top 100 love stories in American cinema history. Casablanca topped the list. Rick Blaine — the iconic, world-weary nightclub owner is played by Humphrey Bogart. Rick’s farewell to Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) remains one of the most psychologically healthy break-ups ever filmed. He chooses principle over possession — what attachment theorists call secure detachment. True love, he shows, isn’t about owning someone; it’s about wishing them well even when they walk away. It’s emotional regulation and moral maturity wrapped in smoky black-and-white.

The West Wing — Josh Lyman and the “Men on Mars” Speech

In this extraordinary sequence from The Warfare of Genghis Khan (Season 5), Josh Lyman played by Bradley Whitford talks to Donna (Janel Moloney) his whip-smart assistant — a blend of warmth, wit, and quiet ambition. “Voyager, in case it’s ever encountered by extra-terrestrials, is carrying photos of life on Earth, greetings in fifty-five languages … including ‘Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground’ by 1920s bluesman Blind Willie Johnson. He died penniless of pneumonia after sleeping bundled in wet newspapers in the ruins of his house that burned down. But his music just left the solar system.” Josh’s monologue, capped by the line “We could send the first representatives from Earth to walk on another planet,” is a meditation on meaning and resilience — how creativity and aspiration survive despair. As a psychologist, I hear in it the essence of post-traumatic growth: the idea that pain, when integrated, becomes propulsion. Like Johnson’s song sailing beyond the stars, purpose allows us to transcend circumstance.

Amadeus — Salieri’s Confession

The film opens in 1823 Vienna. Antonio Salieri (played by F. Murray Abraham), now elderly and confined to an asylum after attempting suicide, is visited by a young priest. Wracked with guilt and bitterness, he recounts his life story — his “confession” — to the priest, telling how his devotion to God curdled into envy when he encountered Mozart’s effortless genius. Salieri watching Mozart compose with effortless brilliance is painful and human. It’s the psychology of envy and self-comparison in its purest form. I see echoes of Salieri every day in young people crippled by perfectionism or “compare and despair” scrolling. His torment is timeless — and instructive.

Good Will Hunting — Robin Williams’ Park-Bench Monologue

After Will (Matt Damon) arrogantly tears apart his therapist Sean Maguire’s (Robin Williams) life in an earlier session, Sean invites him for a walk. They sit together on a park bench by the Charles River. Sean, calm and deliberate, speaks — not to humiliate Will, but to help him understand the difference between intellect and lived experience. When the therapist Sean tells Will that reading about life isn’t the same as living it, it’s the heart of psychotherapy distilled. Williams models therapeutic presence — calm, authentic empathy that pierces defence without aggression. Healing begins, the scene reminds us, when someone finally listens without trying to fix.

The Lion King — Opening “Circle of Life”

That soaring sunrise isn’t just animation; it’s a visual hymn to belonging. Family systems theory tells us identity is forged in connection. The pride, the rituals, the ancestry — all symbolise what every child needs: to know where they fit in the great circle. It’s developmental psychology disguised as Disney.

Pulp Fiction — Travolta and Thurman’s Dance

Vincent Vega – played by John Travolta, a hitman working for mob boss Marsellus Wallace, has been asked to take Marsellus’s wife, Mia, (Uma Thurman) out for the evening while her husband is away. After some flirtatious banter and a tense dinner at a retro-themed restaurant called Jack Rabbit Slim’s, Mia pulls Vincent onto the dance floor for a Twist contest. To Chuck Berry’s “You Never Can Tell,” they perform a deliberately awkward but magnetic routine — part Twist, part mime, part seduction — as the crowd cheers. Why does this scene feel so joyous? Because it’s pure play. Psychologists know that play isn’t childish — it’s life-giving. Dancing in a diner, unselfconscious and absurd, they remind us that spontaneity is an antidote to self-consciousness. Joy, even fleeting, is rebellion against cynicism.

Dead Poets Society — “O Captain, My Captain!”

When students climb onto desks in solidarity with an inspiring English teacher John Keating played by Robin Williams, it’s a cinematic act of moral courage. One person’s defiance becomes another’s permission — the social contagion of bravery. For educators and mentors, it’s a powerful reminder that influence often flowers long after authority has gone.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest — Final Scene

Chief Bromden played by Will Sampson is a long-term resident of the psychiatric hospital who pretends to be deaf and mute to avoid attention. Through his friendship with Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson), he slowly reclaims his voice and autonomy. In the film’s final, unforgettable scene, the Chief suffocates McMurphy—now lobotomised—to spare him further indignity, then escapes by hurling a hydrotherapy console through a window. The escape after McMurphy’s death is heartbreaking and liberating. It captures the universal yearning for autonomy — to reclaim agency even in tragedy. In therapy, moments of change often feel just like that: messy, costly, but profoundly freeing.

Rain Man — “Qantas never crashes.”

In Rain Man (1988), Dustin Hoffman plays Raymond Babbitt, an autistic savant with extraordinary memory and mathematical abilities but significant social and emotional challenges. Raymond is the older brother of Charlie Babbitt (played by Tom Cruise), a self-absorbed car dealer who discovers Raymond after their father’s death. Over the course of their road trip together, Charlie’s frustration gradually turns to empathy and love, as he learns to see his brother’s world through compassion rather than impatience. During their road trip, Charlie wants to fly from Cincinnati to Los Angeles, but Raymond flatly refuses to board any airline except Qantas. He insists:

Raymond: “Qantas never crashes.”

Charlie: “Qantas doesn’t fly to Los Angeles from Cincinnati!”

Raymond: “Qantas never crashes.”

Raymond’s insistence reflects a classic anxiety management pattern — what psychologists call a safety behaviour. When faced with uncertainty (flying), he clings to a fixed, comforting fact: that Qantas, at that time, had a spotless safety record. It gives him a sense of predictability in an unpredictable world. Dustin Hoffman’s refrain is both funny and deeply poignant. It’s a portrait of anxiety management through ritual — what we’d now describe as a compensatory safety behaviour. Long before “neurodiversity” entered common vocabulary, this film invited audiences to see difference with empathy rather than fear.

Monty Python’s Life of Brian — “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

The main character, Brian Cohen (played by Graham Chapman), is an ordinary man mistakenly worshipped as the Messiah in Roman-occupied Judea. After a string of chaotic misunderstandings and failed rescues, Brian is arrested by the Romans and sentenced to crucifixion. Singing on crucifixes shouldn’t be funny, yet it is. This scene embodies cognitive reframing — the ability to find perspective even in absurdity. Humour, psychologists know, is a coping strategy that restores agency when everything else feels beyond control.

Love Actually — Cards at the Doorstep

Juliet has recently married Peter (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor), who happens to be Mark’s best friend. Throughout the film, Mark (played by Andrew Lincoln) appears cold and dismissive toward Juliet (Keira Knightley) — until it’s revealed that he’s been secretly in love with her. On Christmas Eve, Mark shows up at Juliet’s door holding a stack of cue cards. Without speaking (Peter is inside watching television), he silently confesses his feelings. The silent confession of unspoken love — cue cue-cards and Christmas carols — is painful and honest. It’s about longing, restrained by ethics: the tension between authenticity and responsibility. In therapy, those moments when someone speaks their truth, knowing it will change nothing, are among the bravest of all.

Across these scenes runs a single thread: the search for meaning. Whether through courage, humour, sacrifice or joy, each character grapples with what psychologists call existential need — to matter, to belong, to love, to be free. Good films hold up a mirror. They let us witness our fears and hopes at a safe distance and remind us that growth usually begins with discomfort. As a psychologist, I value them not just as entertainment but as empathy machines — tools for understanding why people do what they do.

Because in the end, whether you’re quoting Leviticus in the Oval Office, dancing in a diner, or singing through despair, every one of us is trying, in our own messy way, to find a little grace before the credits roll.

It’s time we stop sugar-coating the digital playground: Kids are being left exposed while policy drags its feet.

Australia’s online world is no longer an optional risk. It’s the default arena for young people’s social lives, identity experiments, peer pressure, and – ominously – mental-health damage.

Australia’s online world is no longer an optional risk. It’s the default arena for young people’s social lives, identity experiments, peer pressure, and – ominously – mental-health damage. So, when our government steps up and says, “Yes, we’ll regulate platforms such as Kick and Reddit,” I applaud it. Finally, someone is saying that if you create a place where kids gather, we have a right to ask: “What are the rules? What are the risks? And what are you doing about them?”

Why Kick and Reddit deserve regulation

Let’s be clear: Kick is not just “another live-streaming site”; it’s a platform where anonymous chat, unmoderated comments, and paid-for “raids” can breed harmful behaviours. Reddit is not simply benign “forum talk”; it hosts adult sub-communities where myths, self-harm encouragement, extremism, and exploitative content go unchecked.

The government is right to say: if you provide a public stage, you bear public responsibility. Too many platforms have enjoyed “wild west” conditions: minimal age checks, minimal moderation, and maximum profit. Meanwhile, kids are sinking into anxiety, self-harm, distorted body image, addiction to “likes” and “views”. I’ve watched it for three decades. The lights are flashing red. (Central News: Read here »)

Regulating Kick and Reddit isn’t about censorship—it’s about accountability. If you open the door to children, you should not slam the door on safety. The legislation must ensure platforms:

• verify ages properly and effectively;

• moderate high-risk content (self-harm, exploitative streaming, sexualisation);

• ensure privacy, but not at the cost of kid-protection.

So why is Roblox still outside the fire-hose?

Here’s the kicker: for many children, one of the most dangerous digital environments remains unregulated: Roblox. It’s marketed as “safe for kids”. It looks like a game. But the lines between play, social chat, live micro-transactions, user-generated content, and peer pressure are blurred. Let’s unpack the risks:

• Millions of under-16s are on Roblox. It’s their social space, entertainment space, chat space.

• They encounter unmoderated “rooms”, user-generated games with scant oversight, avatars that push cosmetic purchases, peer-led pressure: “buy this, join this, get likes”.

• The environment conditions them for the same problematic behaviours we see on “adult” platforms—addiction, comparison, social isolation.

• Yet current policy treats Roblox like a toy, not a platform. It’s outside the regulatory gaze.

That’s unacceptable. If the message is “we’ll regulate platforms that influence young minds”, then leaving Roblox exempt is a glaring inconsistency. It’s like regulating violent video games for adults but exempting candy-floss because kids “like it”.

We must match policy to reality.

To the policymakers: you’re on the right path. But take the next step. The logic that brought Kick and Reddit into scrutiny must apply everywhere young people gather online—including “games” that double as social platforms. If you’re worried about over-reach, fine—let’s carefully carve definitions: “platforms where minors engage in chat/live transactions”, “user-generated content with peer network features”, “in-game monetisation targeted at children”. But carve them consistently, not with loopholes.

And to parents and educators, I say: regulators can legislate, but you still hold the frontline. Talk about online spaces not as “fun” or “harmless” but as social zones with rules. Ask children: “Who are you talking to? What are you buying? What are you doing for likes? How often do you stop?” Keep the conversation alive.

Because at the end of the day, the biggest risk isn’t the platform—it’s the young mind unprotected, unmonitored, thinking “this game/social space couldn’t hurt me”. It can. And unless we bring policy, platforms, and parenting into alignment, we’ll keep putting kids at risk.

Regulate the wild west. Level the playing field. Protect the young.

Australia is doing the right thing by calling out Kick and Reddit. Now let’s finish the job and include Roblox — because our kids’ safety doesn’t get exemptions just because the logo is cute.

Celebrate the End of Exams – Not Just the ATAR

Every year, thousands of exhausted Year 12s stumble out of their final exam rooms, eyes glazed, brains fried and hearts pounding — only to be told: “Don’t celebrate yet. Wait for the results.”

Every year, thousands of exhausted Year 12s stumble out of their final exam rooms, eyes glazed, brains fried and hearts pounding — only to be told: “Don’t celebrate yet. Wait for the results.”

What absolute nonsense. We should be celebrating now — not because of a number that arrives in December, but because they’ve just completed one of the most demanding endurance events of their young lives. The exams are done. The pressure cooker is over. That deserves recognition, not another month of purgatory.

Let’s be clear. Year 12 exams have become absurdly over-hyped — inflated into a supposed measure of intelligence, worth and future success. In reality, they test how well you can recall and regurgitate information under artificial, time-pressured conditions. They measure memory, technique and exam temperament — not creativity, emotional intelligence, or resilience.

And let’s not forget the glaring inequities: access to tutors, calm home environments, supportive schools and mental health stability all play massive roles. The ATAR isn’t a measure of capability — it’s a snapshot of performance in a narrow window of time.

The truth? Year 12 exams measure how well you can play the game. They reward those who can decode marking rubrics, spot past-paper patterns, and manage their nerves. Those are useful skills, sure — but they’re hardly the full story of human potential.

Some of the brightest, most original thinkers I’ve met weren’t top-scoring students. Many didn’t peak at 17 or 18. They bloomed later — once they found a path that matched their strengths, passions and temperament.

In 2025, there are dozens of ways to get where you want to go.

Bridging programs, TAFE pathways, early-entry schemes, apprenticeships, micro-credentials — the traditional ATAR-to-uni pipeline is just one route among many. Employers are increasingly valuing character, creativity, collaboration and digital literacy over a number on a piece of paper.

The world has changed. Our young people know it. It’s time parents and educators caught up. So, if you’ve got a Year 12 student in your life, celebrate them now. Book the dinner, bake the cake, give them a hug and tell them you’re proud — not because of what they scored, but because they showed up, persevered, and survived one of the most stressful rites of passage in Australia.

The results will come and go. But the grit, growth and self-knowledge they gained this year? That’s the real achievement.